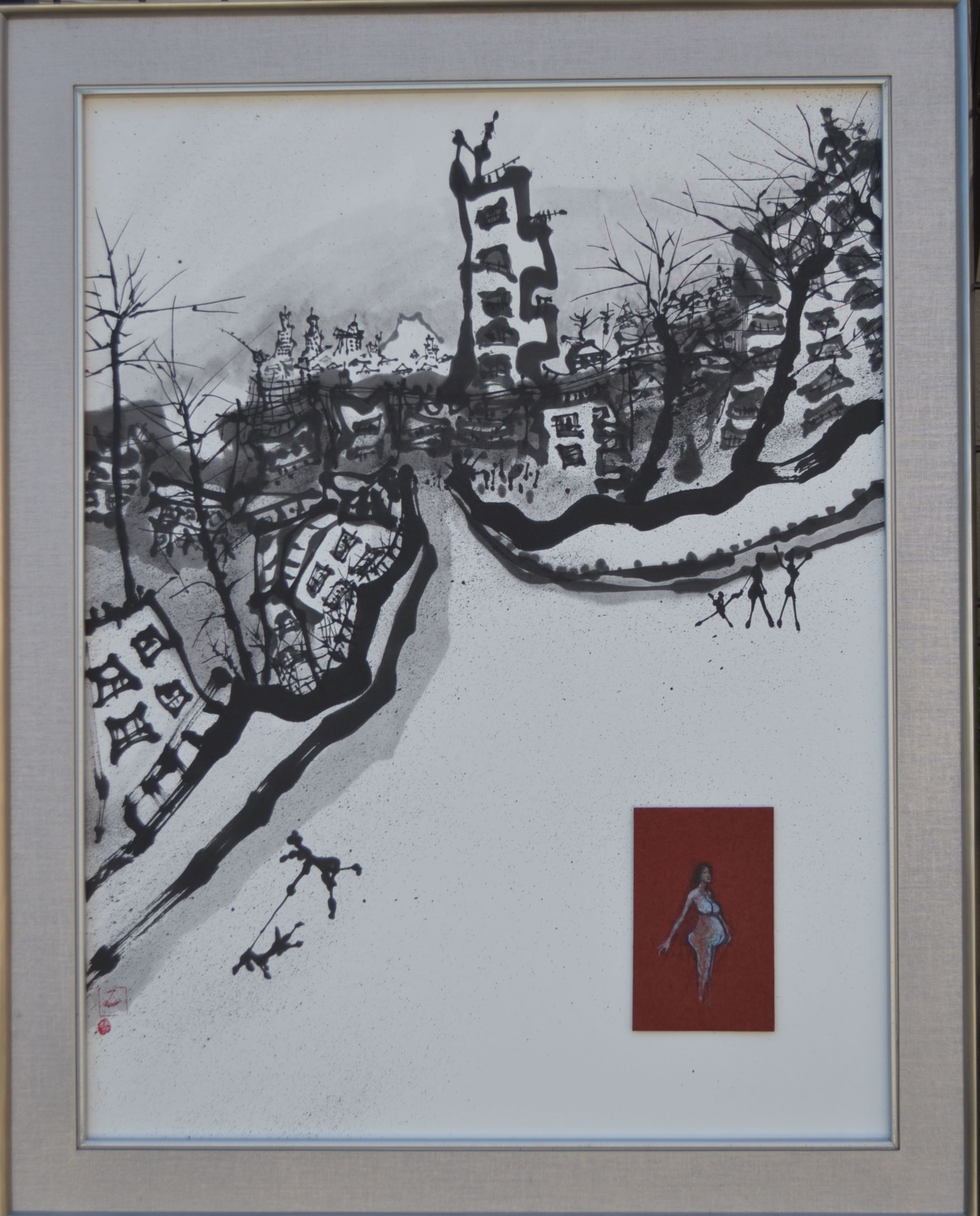

Ameyoko Backstreet Exhibition October 2016

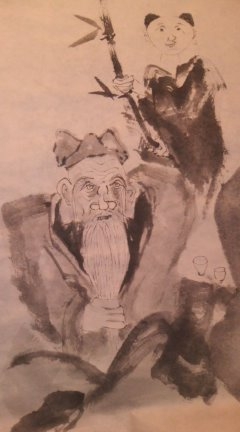

I was an oil painter in New York. 25 years ago I studied ink painting from a very old man across the street from the Yoshiwara.

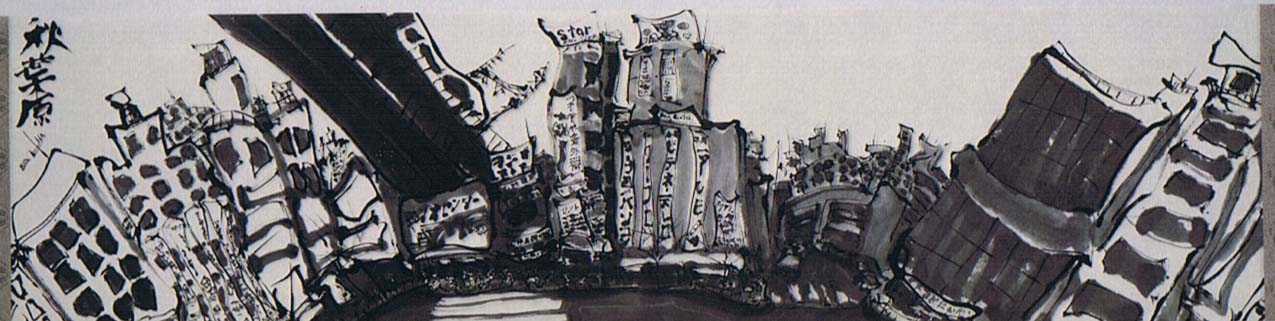

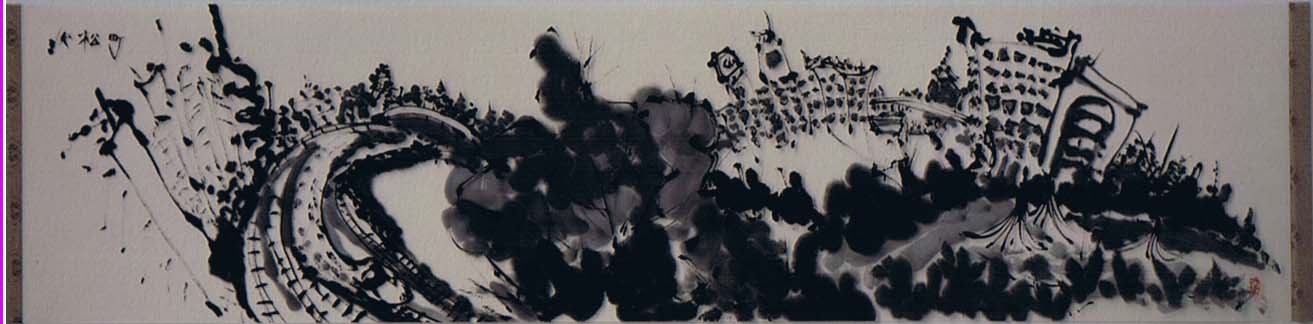

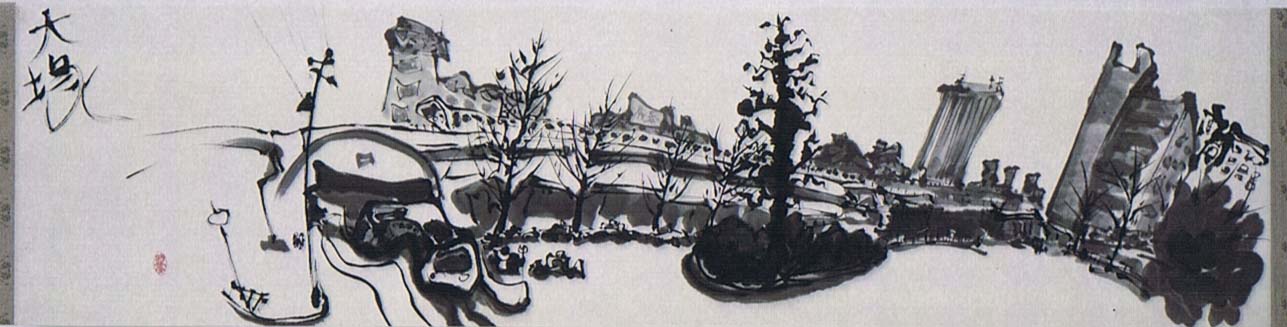

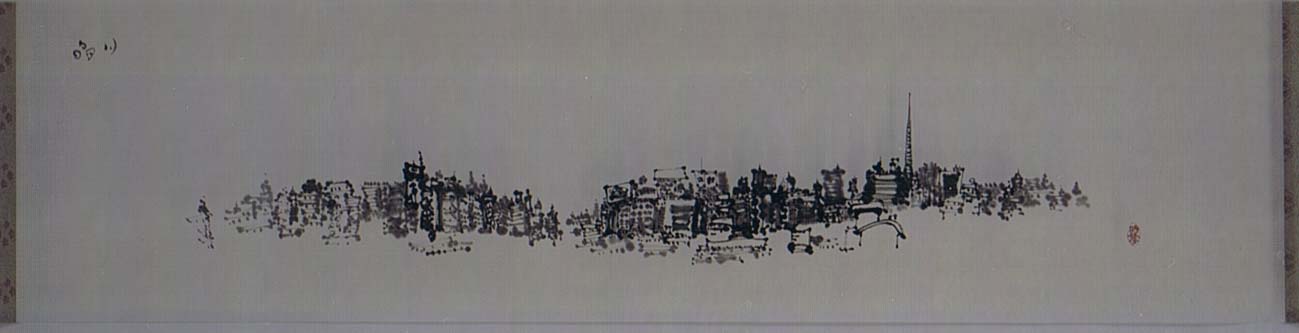

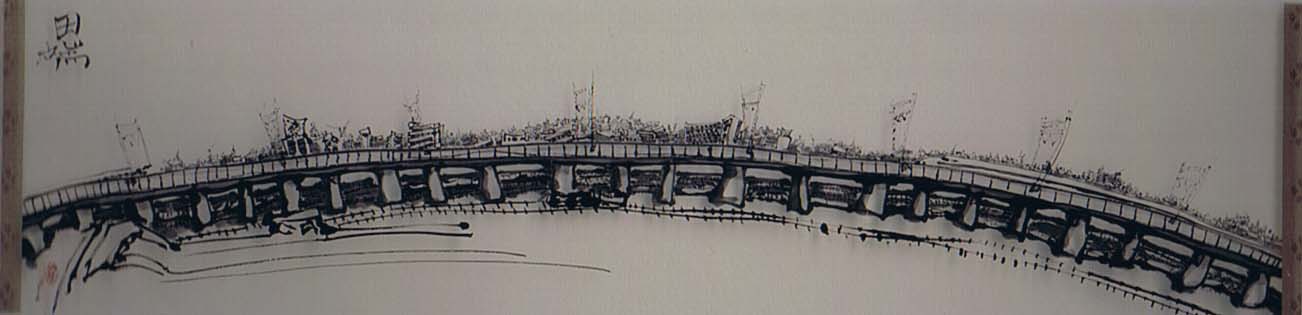

Tokyo has been my subject. Tokyo has been my passion. I painted the 29 Stops of the Yamanote Line in 1995, the 18 Bridges over the Sumida River in 1997, The Stone Men of Yanaka - Jizos that live on the street in 1999. Two years ago I painted Ichiyo's shortcut through Yanaka.

My paintings come from where I live.

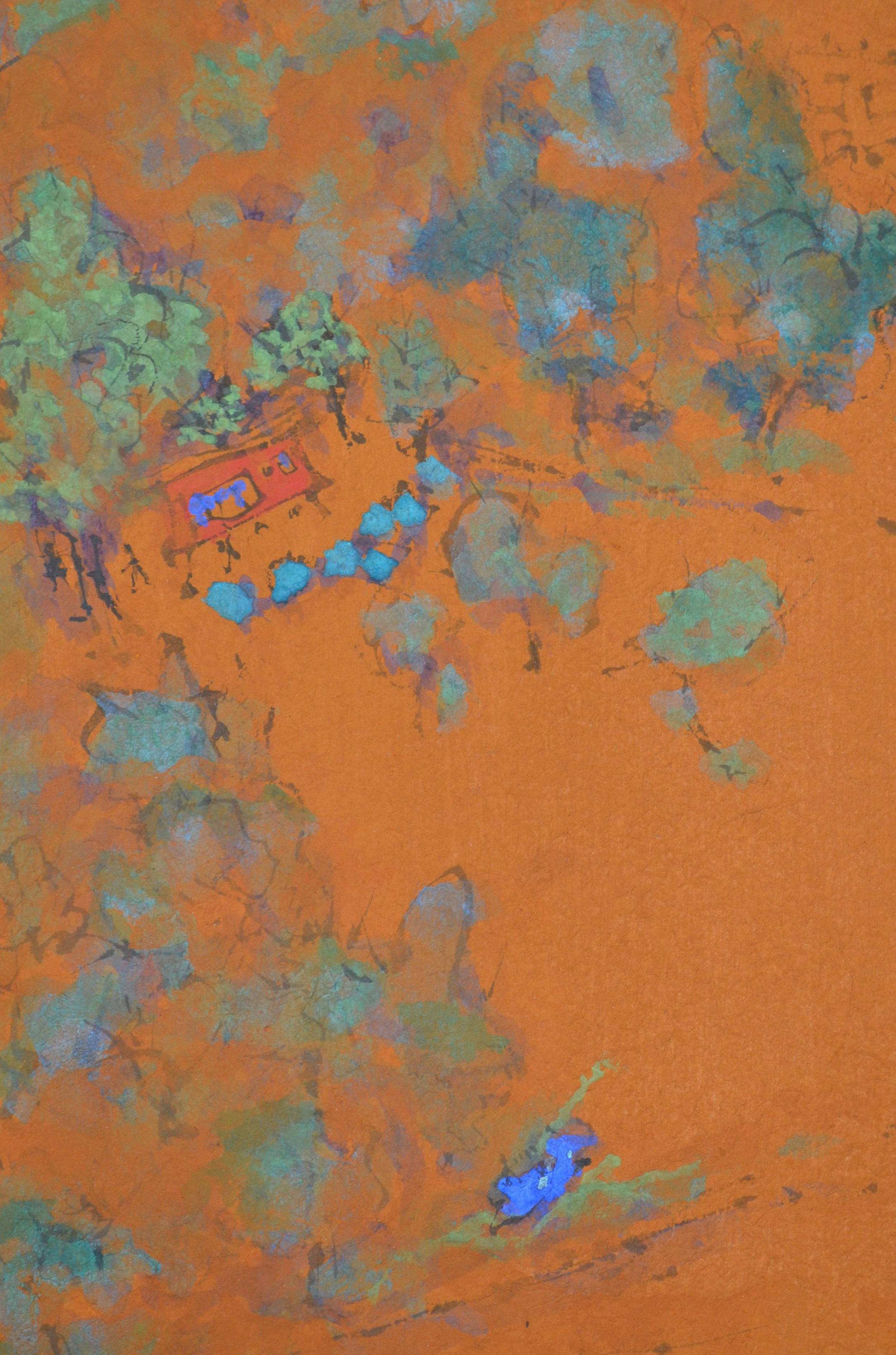

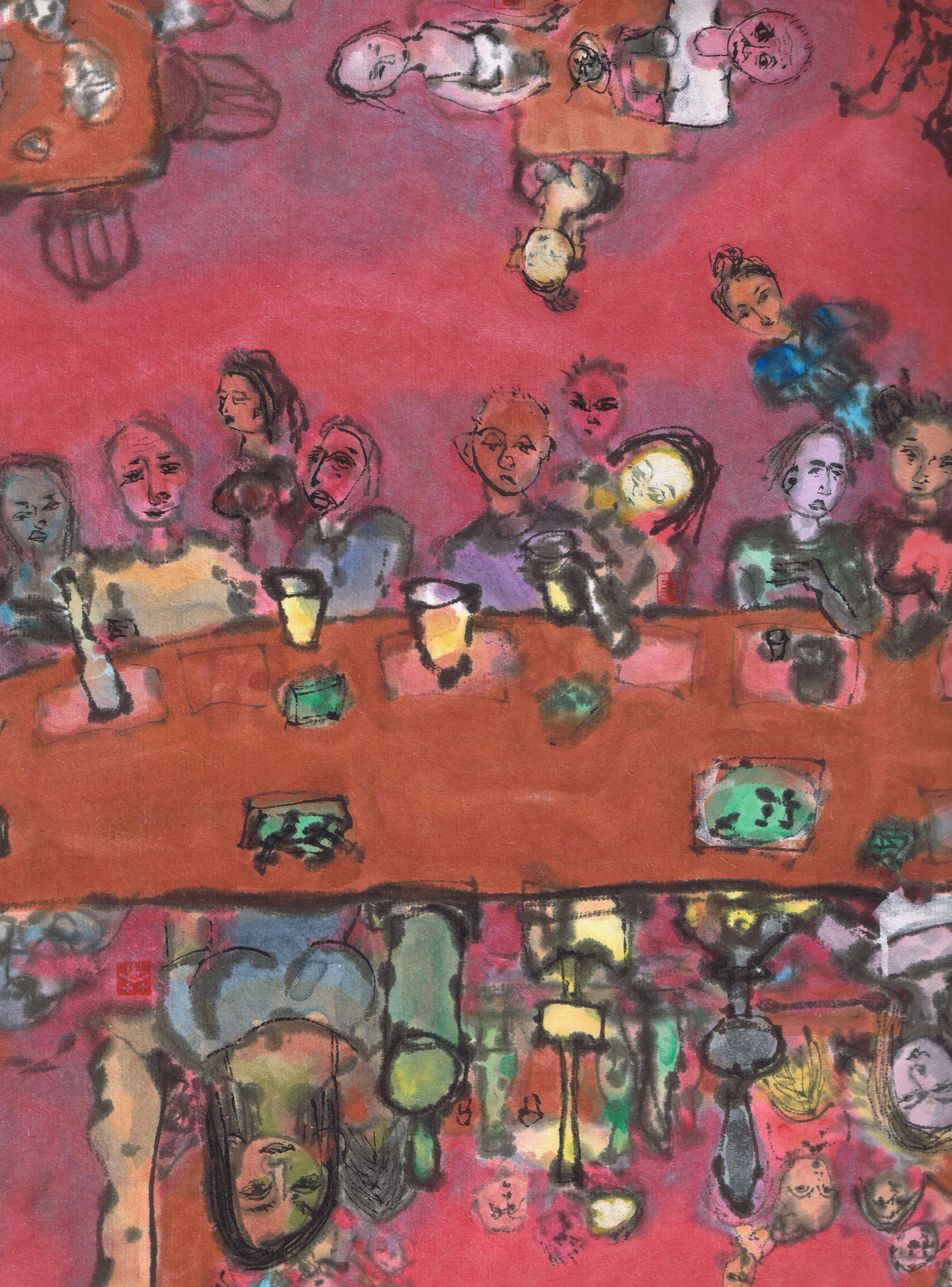

Ameyoko is beside the tracks in Ueno. After my divorce Ameyoko became my living room and my garden. I live in the streets. I live in the bars. Crowded, full of life. In the Ameyoko, even the main street is a backstreet.

About the materials - Sumie is the most direct and sensitive painting material I know. Sumie is very old, but it is alive. It is new.

But what does it all mean?

Balthus, a European painter famously said, "Painting is a language not easily translated into another."

Fare warning.

This year I will make an exhibition in October.

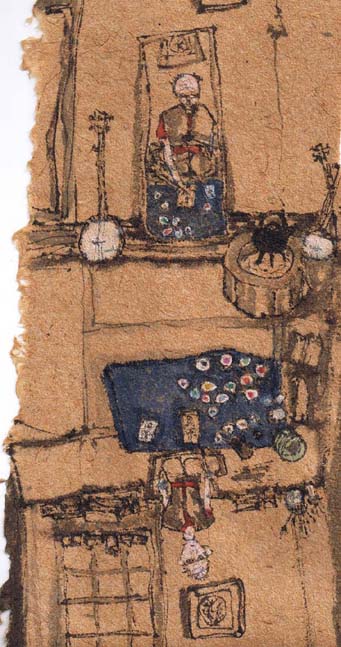

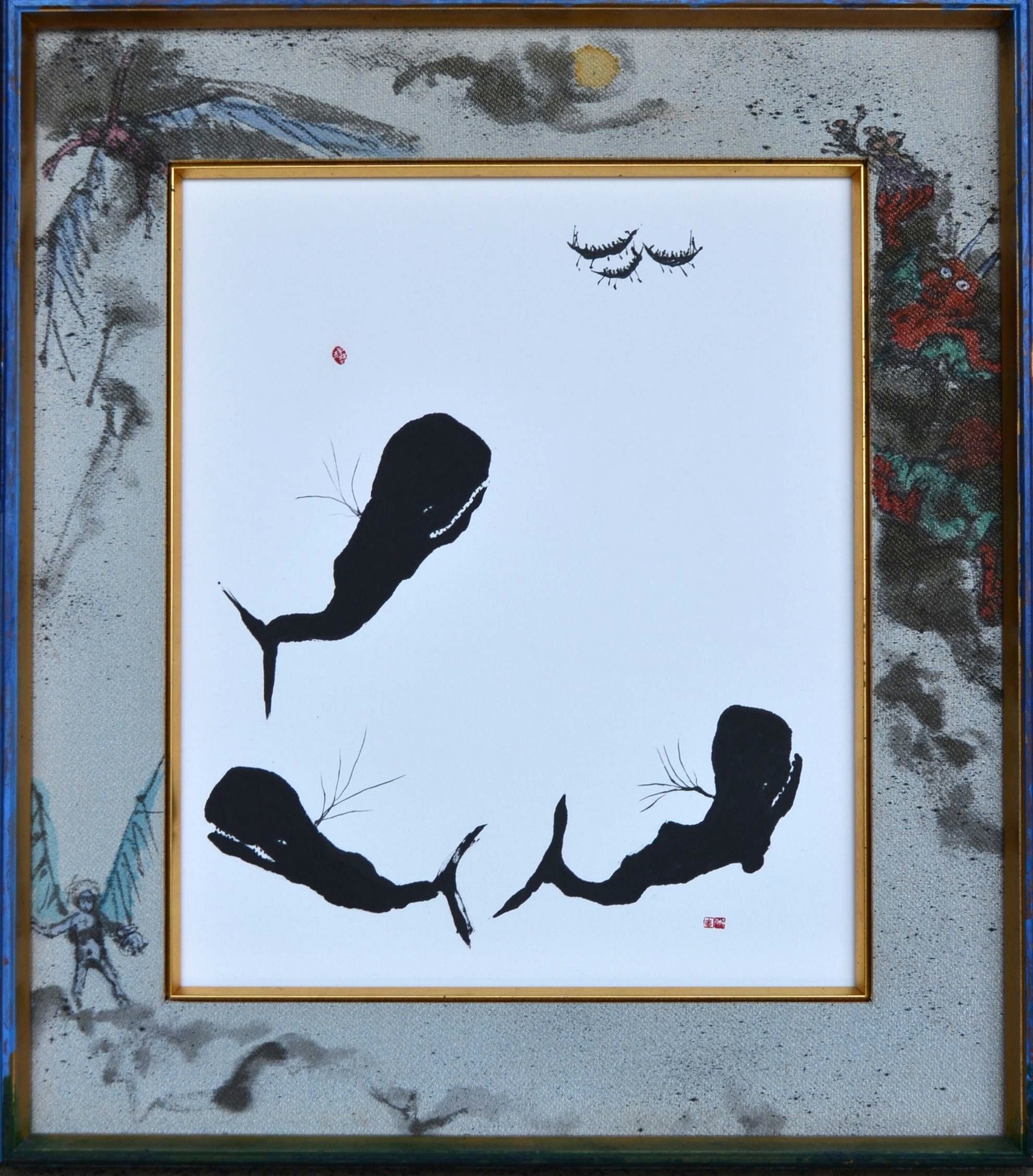

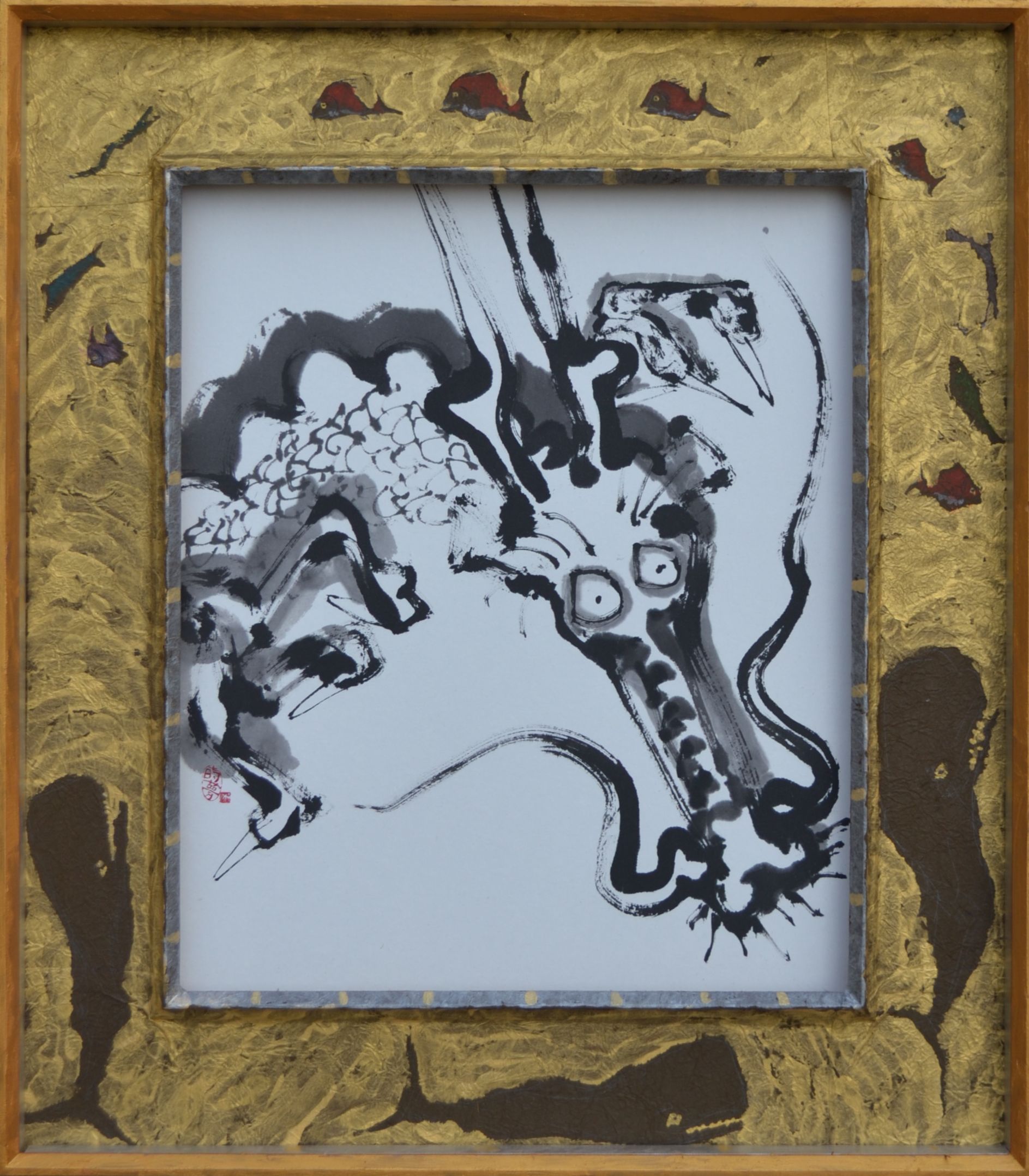

I studied scroll making in Japan. Part of that study involved the visiting museums to see how the great scroll were made - The mix of texture and color, the interaction of central image and the cloth that surrounded it. A curator friend of mine told me that a scrap of an old piece of cloth can cost as much as a sports car. Its beauty and importance cannot be undervalued.

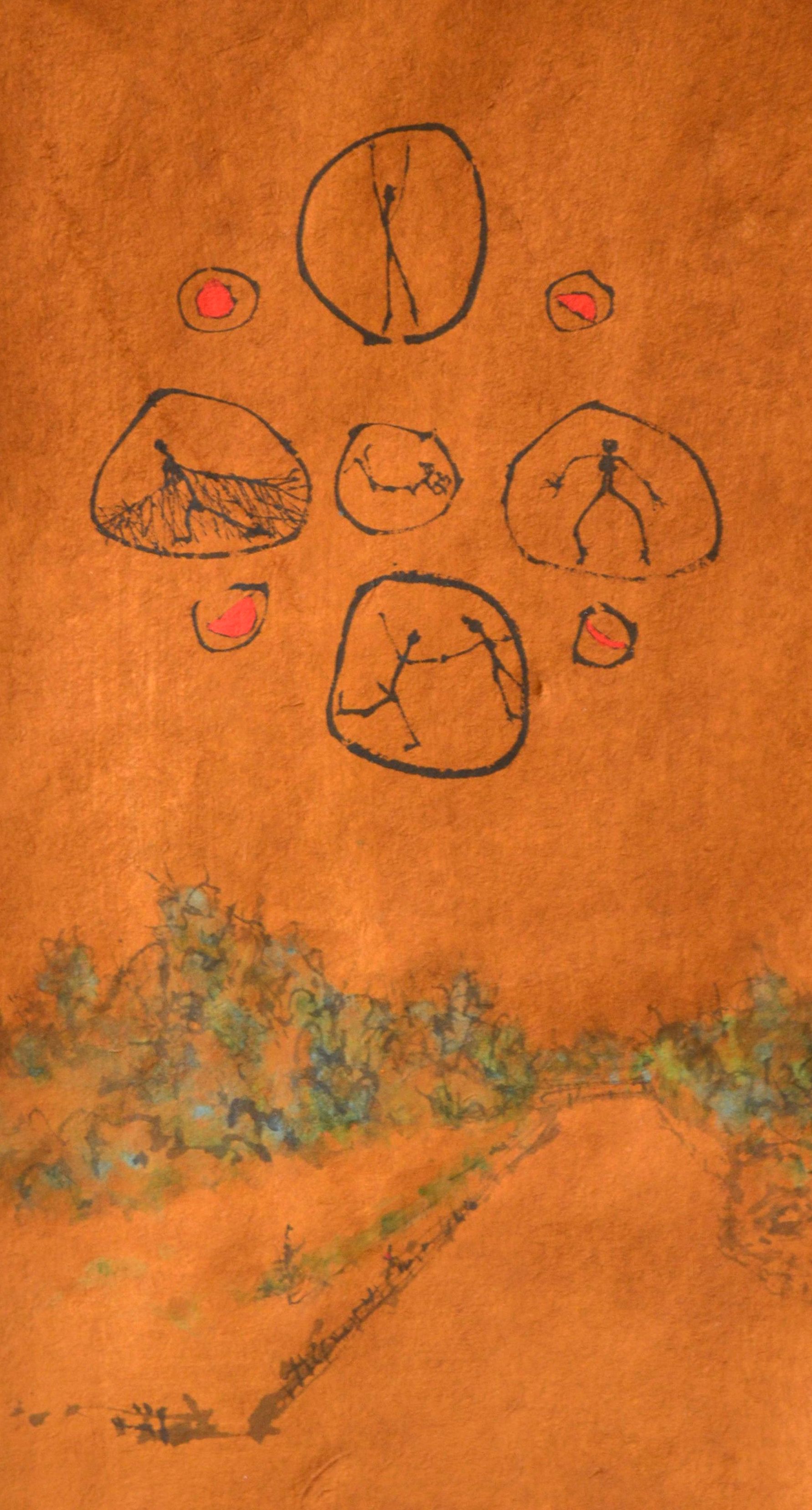

My current exhibition is very much about the relationship between a painting and its frame, their communication and balance. I have tried to bring the aesthetic of scroll making into the work I am doing - color and texture, the interaction of figurative and abstraction.

2015

2013

Ichiyo's Kumade 2013

In 2013 my show was titled, Ichiyo's short-cut through Yanaka. The idea for the show came from reading Higuchi Ichiyo's books and even more from reading her diary. Everyone in Japan knows Ichiyo was a famous writer, more know the romantic story of her life than her actual books. She was a young lady who wrote books about the lower part of town, from the time she and her mother and her sister had to move down there, near the Yoshiwara, the famous licensed district from Edo. Ichiyo lived about 100 years ago. She lived for just 24 years, the number of years I had been in Japan. Reading her diary I discovered she lived in the same space I did, and walked the same streets, went to the same festivals, walked beside the same lotus pond i enjoy today. The people in her stories were my neighbours. I began to feel she was here, one step ahead of me, just out of reach, turning a corner before i could get to it. She was shocked in her time by how quickly Tokyo was changing, just as we are today.

Lotus 2013

In the spring of 2013 I was flattered to be invited to exhibit my works in the Nakanosawa Museum in Gunma. The museum is a pentagon, great tall walls and an upstairs gallery along the back two. I noticed that in previous exhibitions artists did not take advantage of the wall, and preferred to exhibit at eye level below the mid beam. I planned to exhibit my Yamanote paintings below the beam. My challenge was above the beam — those great tall walls.

I decided above the Yamanote stations I would paint dragons. It was my first idea about the train line that roared below the windows of my first Tokyo studio like metal rumbling dragons.

The main walls at the museum were about 60 feet wide. The space above the beam was over six feet tall. A gat challenge, made all the more so by the dimensions of my studio. I work in a little tenement row house, the Japanese call it a "nagaya" a long house, as usually two to four units are stuck together on the back alleys of the lower parts of Edo. My nagaya was built in the Taisho Era, it survived the great earthquake and the firebombing of Tokyo by the Americans. It is a little wooden shack. My floor space for painting is about 5 feet by 7. It is a good size, but how to use it to paint sixty foot paintings.

It took some planing and a whole lot of rolling and unrolling. But in the end it worked out fine.

Hidden Voices 2012

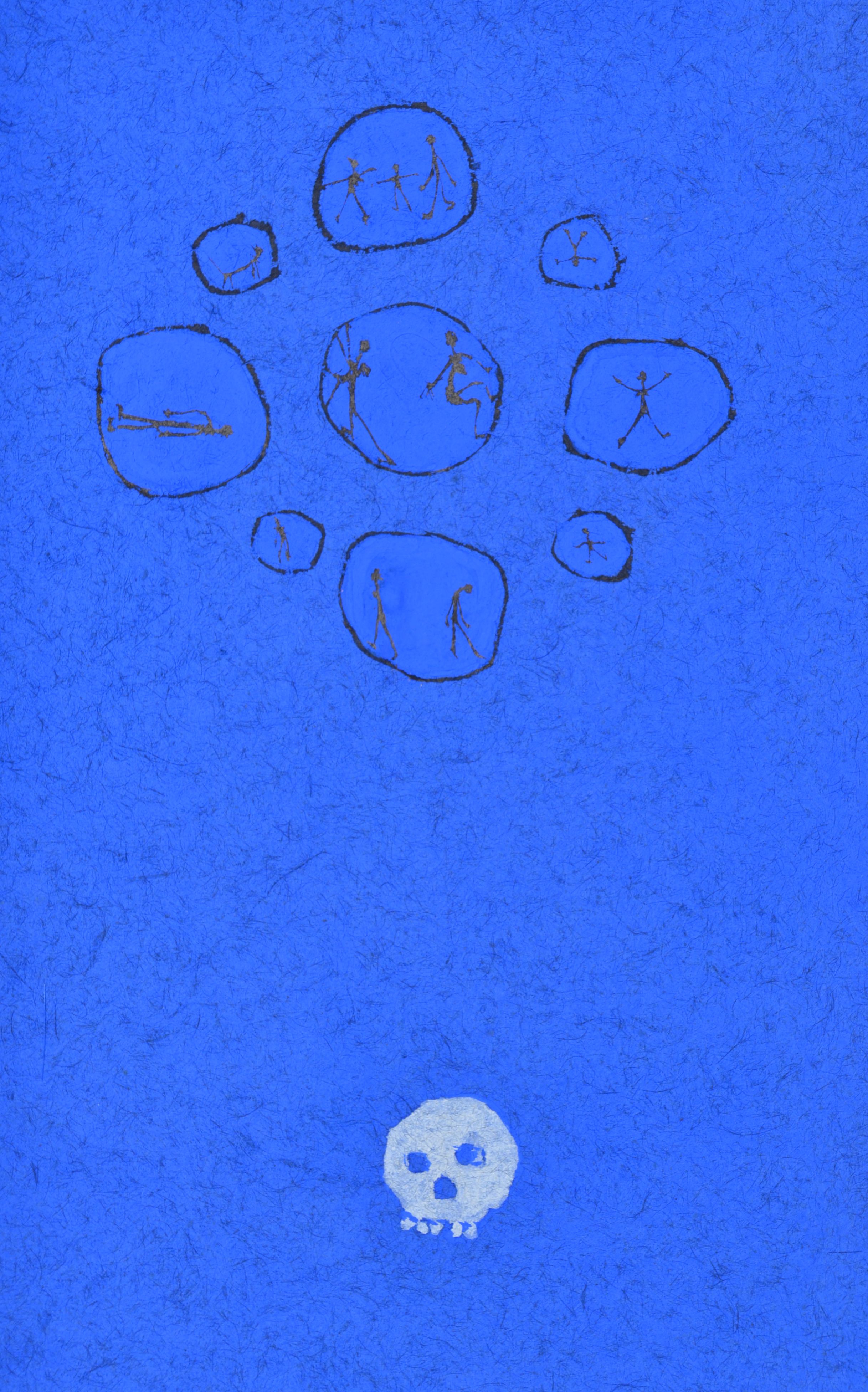

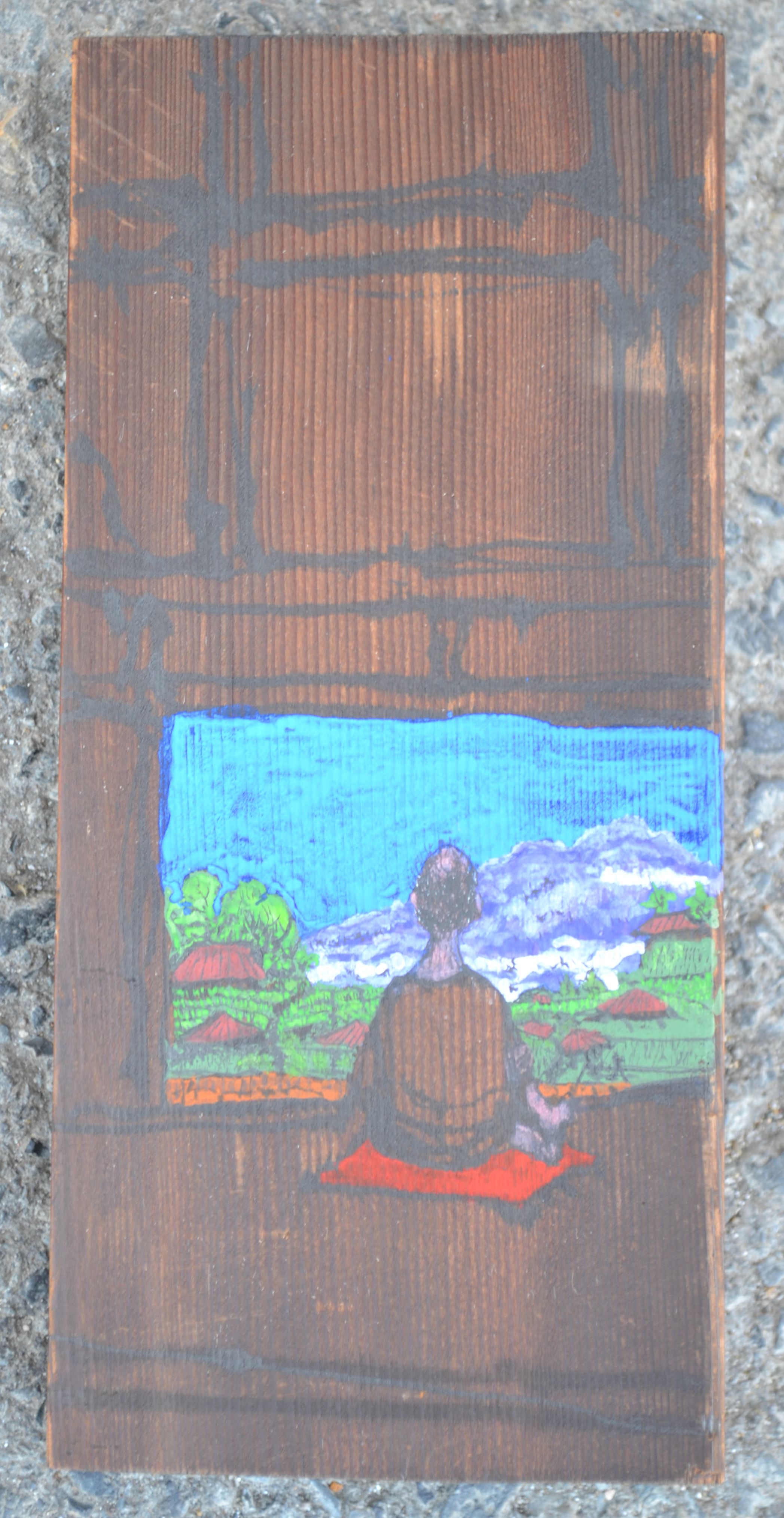

My expiation in 2012 was called Hidden Voices, it is a continuation of a theme I have visited and revisited over the years, exploring what is inside and what is out. What is a frame and what is a painting. Perhaps this interest began who I started to study Japanese scroll making some 25 years ago. The beauty of a Japanese hanging scroll can sometimes be as much from the scroll as from the painting contained inside it. This particular exhibition was inspired by a grand old kiri tree, recently cut down in my garden.

Kiri, Paulownia trees have a special meaning in Japan. And they have special uses.

In the old days a man would plan a paulownia tree when he had a daughter. Paulownia trees grow quickly, and are the work that Japanese used to use for cabinetry. It is light, strong and fire resistant, an important quality in a country perpetually quaking and burning. The tree was planted to be large enough to cut when the daughter was 20 years old, to make a tansu, a dresser to hold the daughters clothes where she was sent off to be married.

The kiri tree in my garden was a grand old thing, and as with every great tree it had a spirit. It was a family tragedy when it was cut down. It had grown into the foundation of the house, and the landlord decided it had to go.

I asked the men that cut the tree down if I could have a piece, for my memory. They asked which piece. I said, all of them. I piled the old tree where it used to stand, and eventually these paintings came out of it.

My third exhibition in Japan was the first with a set theme. It was the project that made me an ink painter. My first exhibition had been of oils, landscapes mostly and was in the ginza, by the time I staged it I was already changing. My second exhibition was held in Yanaka, in a little gallery converted from an old pawn shop. I was using ink and I was using color, but mostly I was using them in the way I had been taught to use oils and the way I had been taught to use charcoal.

in the Sumida Park Riverside Gallery 1996

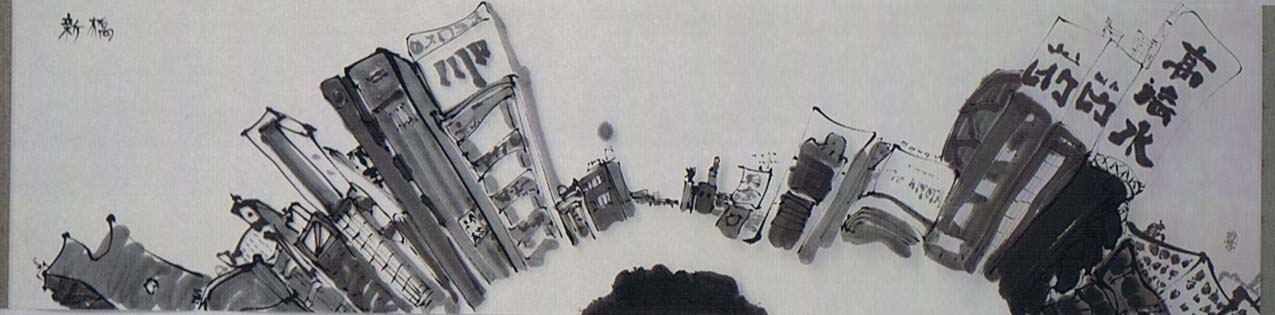

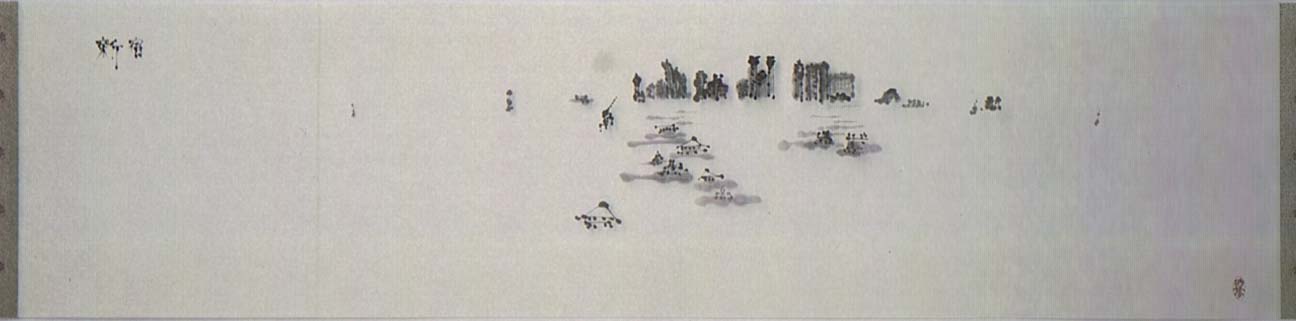

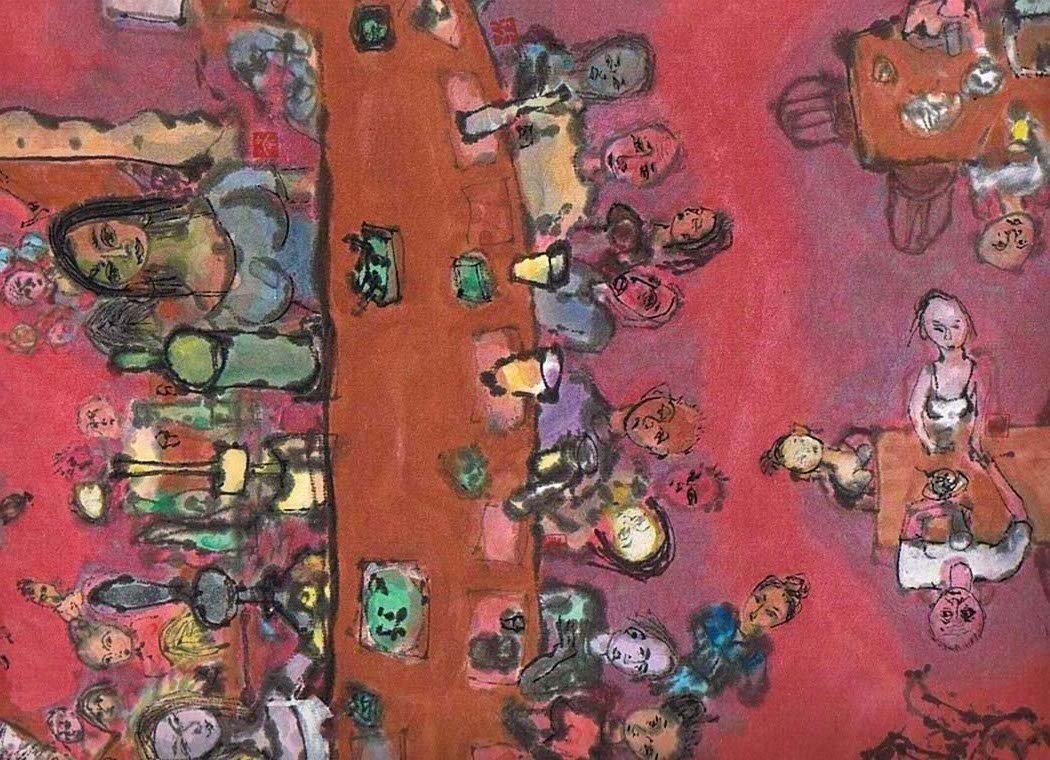

My third exhibition was called The 29 stops of the Yamanote. I decided I would paint every station of the JR Yamanote train line. The Yamanote line circles central Tokyo. Tokyo is not a city. It is a series of towns that have intertwined around what was the Edo castle. The Yamanote circles through most of them. It is the most ridden train in the world and it goes nowhere at all. If you stay on board for an hour you are back where you started. It is a circle and forms a mandala, a noisy rattling prayer, out of the city of Tokyo. But these are not the reasons I wanted to paint it.

I wanted to paint the Yamanote line because so many millions ride it every day, but no one seems to see it. It is like your husband's or your wife's face after fifty years together. It is there but you never look up to see it. My contention as a young ink painter, as an artist, was that everything is beautiful if you just look at it.

So I set out, riding and stopping, sketching and returning back to my studio to my sumi ink and paper. It took me a year of sketching, and painting and sketching and painting.

One of the most popular questions I am asked is how long it takes to paint a painting. It is not simply answered. The station that caused me the most problems of the 29 was Tokyo station. It was the most difficult because it was the most outwardly beautiful, and the most painted. Most any sunny day you can find half a dozen artists outside one part or another of Tokyo station painting away. What could I see that they didn't? What could I add to the conversation?

I sketched it and painted and threw out the paintings and went to sketch it again. After three months of this I gave up. I was totally beaten. I threw out my sketches. I threw out all my paintings and lay down flat on the tatami mat of my studio floor. I lay there that August afternoon, totally beaten. I gave up. Then a funny thought came to me. I sat up and in less than a minute I had it painted.

So how long did that painting take? Did it take the 15 years I had been studying art? Did it take the three months I had been trying and failing? Or did it take the fifty three seconds I had actually held the brush to paper?

Tokyo Station

The full series of 29 stops took me a year to complete. I painted every station with the same brush, and the same ink, and on the same kind and size of paper. I put them all together and noticed that they were really boring. This had not been my intention. I threw them all in the garbage. And started the whole thing again. This time determining to make each one special. Each would be painted with a different brush, a different in and on a different kind of paper. Each painting would be from a different point of view.

Japan makes more kinds of paper than any country in the world. When I made those paintings I was blessed with a richness, a variety of papers made in different ways by different craftsman in different parts of the country. I fear we are loosing another of these craftsman every day. It just doesn't pay. Too many machines, imports, cheap substitutes. Craftsmanship without reward does not so much interest the next generation.

But I had a great variety to choose from, as well as ink. In American art school I had learned that black was black. In Japan I learned that black has an almost infinite variety of shades and colors. The ink sticks I rubbed against my stone were made by dozens of different craftsman, and all by hand, as were my brushes.

some of my sticks of ink

I determined to go out and see. I determined to put the same effort into seeing that the craftsmen had invested into making my materials.

In another year I had finished.

I took the paintings home to show my wife. She carefully looked through them and said it was a stupid idea. No one wanted to look at the Yamanote line.

It was a little disheartening. But then she said as long as I had gone to all the trouble to make them I might as well put them on a wall and see. She surprised me by getting the head priest of the Kanegi Temple to our house to see my paintings and to give us his suggestions. then he introduced a gallery.

A long story shortened, I got a space, a long space, like a station, in a newly opened community gallery along the river. Staging the first exhibition there was also a story, as was the fuss that followed. It turned out to be my best received, best attended, best covered of all my exhibitions in Japan. People came from as far a way as Kyushu and Osaka to see it.

And my wife had to admit that someone did want to look at the Yamanote.

Some of the 29 Stop of the Yamanote

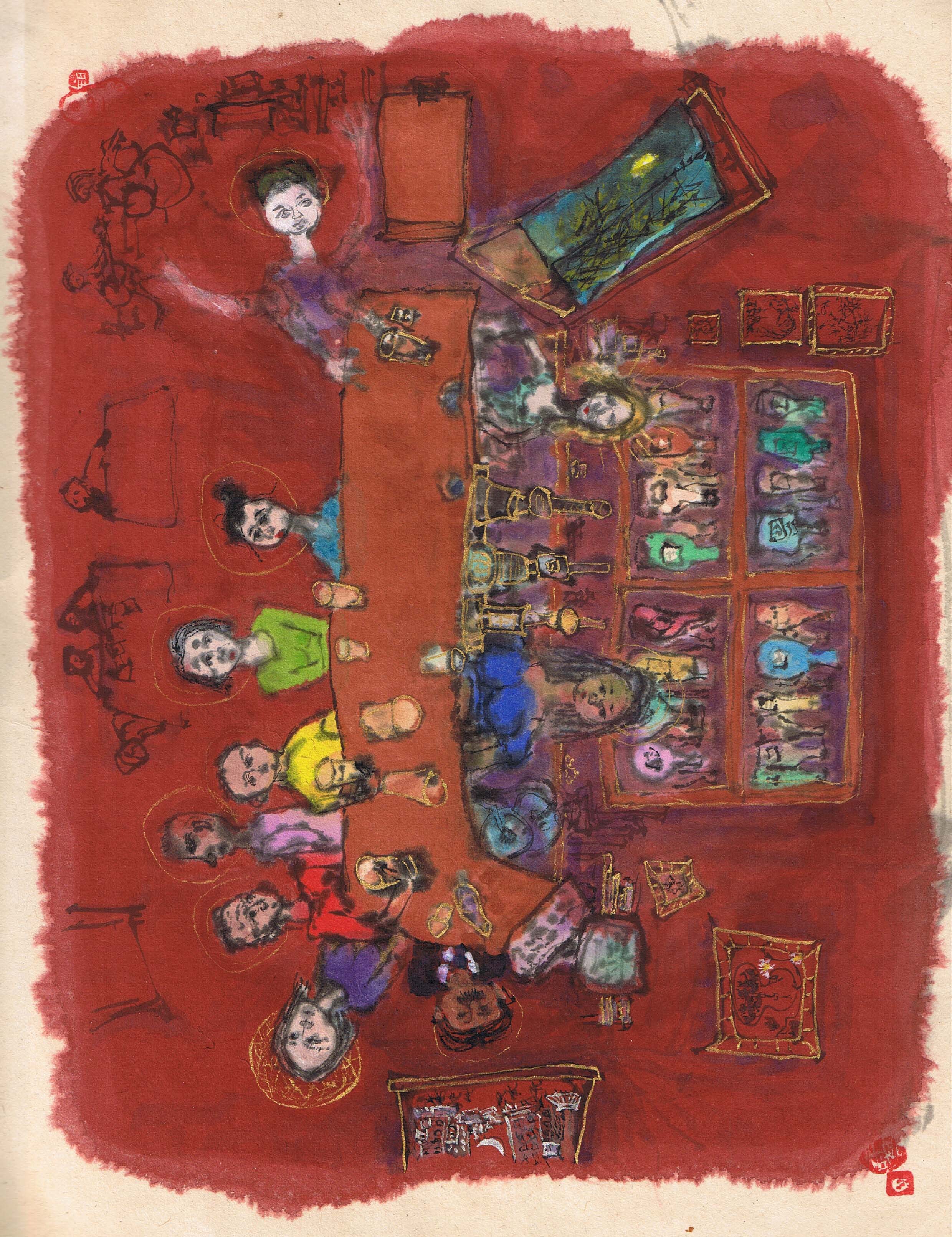

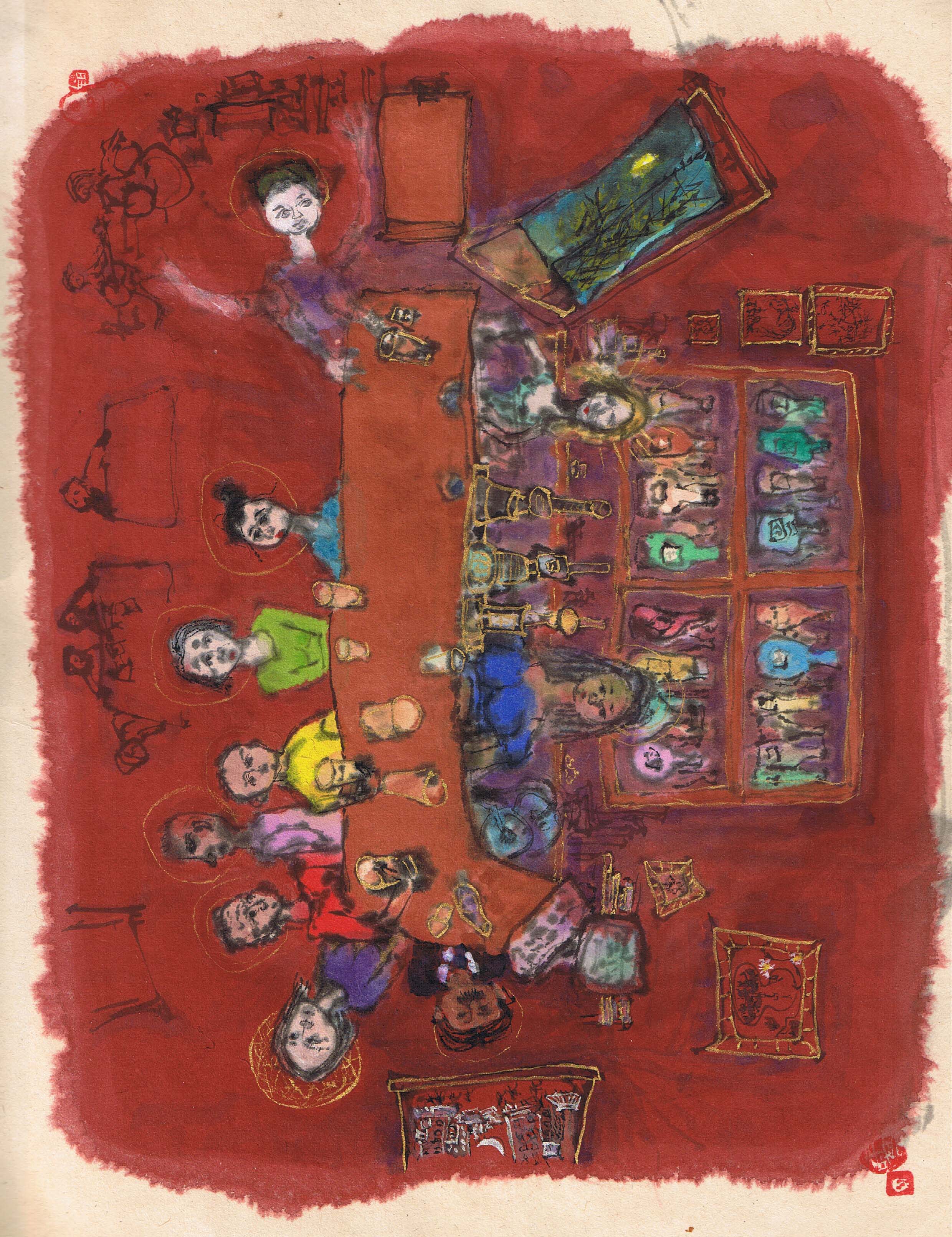

In 2010 I started painting upside down. Not so much upside down as every way up. It fit a painting I was making of inside an English pub in Ueno. In this pub everyone has an opinion. And every one is always right. Frights happen. Chairs get broken. Heads get dusted. I paint from everyone's point of view.

From the customers at the bar,

The end of the bar,

From the French gals pouring beer and conversation.

Paintings this year were of sumi ink on washi, with color.

And the paintings were folded with words on all sides like an every direction book and hung on sticks like kites. Visitors to the exhibition we invited to turn the painting around for different points of view.

October in Yanaka, 2014, my mandala

What painting is not a dream? What painting is not a prayer? My mandala are wheels within wheels, paintings within paintings, frames surrounding frames. An image speaks to the one beside it, and each becomes more for the communication. I will exhibit 25 new paintings, using sumie, nihonga, oil, tempera, It will be part of the Geikoten group as it has been for the last twenty years. ArtLink this year seems defunked.

The October art exhibitions in the Yanaka district of Tokyo have changed. For the first time since 1997 the ArtLink group will not be making an art map or mounting a neighbourhood exhibition. The local Geikoten group continues with map and exhibitions but have cut back, severely limiting exhibitions included. They are going go back to basics, making it truly a neighbourhood event.

These art cutbacks are happening as Yanaka is mired ever deeper tourists, Japanese and those from overseas. New galleries, new coffees shops, guest houses and cute little wine bars seem to be opening every day. The Lonely Planet included a walking map highlighting once deserted back streets in their newest Japan guide. Some folks have taken to calling the Yanaka, Sendagi, Nezu neighborhood, "Yanakaland." I know I have.

The thing I liked best about the Yanaka art groups is their anarchy. We do not follow any particular material, theme, or school of art. We are collected geographically, in this great old art, formerly inexpensive, part of Tokyo. Home to the first imperial art school of Japan, and various art and literary notables: Okakura Tenshin, Takamura Kotaro, Yokoyama Taikan, Mori Ogai, and that guy that wrote about the cat, as well as the contemporary, Donald Richie.